Motor Cycle Training in the Grounds of Tredegar House

Article submitted by Steve Barber

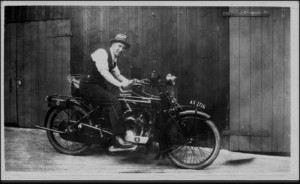

During the 1960’s and through the 1970’s I was involved in training people to ride motorcycles on the Home Farm Roads of Tredegar House. Most of the instructors were provided by experienced voluntary members of a Newport motorcycle club under the auspices of the Royal Automobile Club and the Auto Cycle Union. This training scheme was a branch of a national organisation, with similar schemes taking place over the U.K.

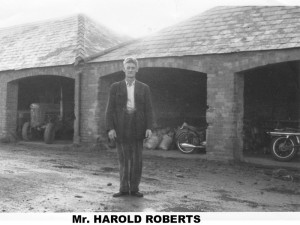

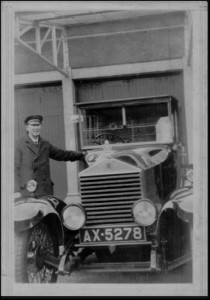

The local scheme was also run with the help of the then Newport Borough Road Safety Department, controlled by a Sergeant of the Newport Borough Police force. Theory lectures were given to the trainees, once a week, in the Police lecture room at the Newport Civic Centre, with training films also being shown. Members of the Newport Police Motorcycle Patrols also assisted with instruction, and shepherding the trainees on the roads surrounding Tredegar House. The practical training was, for many years, organized by a Mr. Harold Roberts (see photograph).

Many of the trainees used their own machines, but for those who did not possess a motor cycle, the Scheme had about three small training machines for pupils use. These machines were kept in the old stable block at the rear of Tredegar House, with the permission of Mr. Cullimore of Home Farm. Who also allowed us use of the farm access road, running through to St.Brides Road.

The usual courses lasted about three months and the practical training took place on two evenings a week. Lectures and training films were usually given on a Monday night in the police Lecture Room at the Civic Centre. Fees charged for the courses were minimal, usually between two or three pounds.

The training scheme ended with a practical test, held at the Tredegar House venue. Pupils were tested for their riding ability on the private and public roads. They were expected to demonstrate skill in riding and controlling the machine, including being tested in maneuverability control in slow riding. They were also tested for their knowledge of the Highway Code and expected to have an understanding of elementary maintenance of motorcycles. The appointed Examiners were all experienced motorcyclists, members of the R.A.C. and a police officer for the Highway Code.

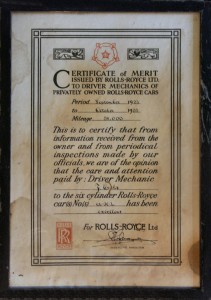

The tests were quite strict and only the trainees who showed a high level of skill received a pass mark. All trainees who received a pass were presented with an ornate certificate and a button-hole badge. These awards were presented at a special prize-giving event, held late in the year, at Newport Civic Centre. Presentations were made at this event for the annual Newport Road Safety Rally, school children’s Safe Cycling Awards and the Motorcycle Training Scheme. Newport’s Mayor, members of the town Council and the Chief Constable and Road Safety Officer attended this event.

Pupils who passed out successfully on this course normally had no difficulty in passing the Ministry of Transport Driving Test. However, responsibility for training motorcyclists was eventually taken over by the road Safety Department of Gwent County Council. Training in the grounds of Tredegar House then ceased.

Users Today : 34

Users Today : 34 Users Yesterday : 64

Users Yesterday : 64 Total Users : 88230

Total Users : 88230 Views Today : 75

Views Today : 75 Total views : 597822

Total views : 597822 Who's Online : 1

Who's Online : 1